“We Don’t All Have the Same 24 Hours”: How Temporal Privilege Keeps Inequality Hidden

There’s much talk of time divides, but inequality isn’t just about hours on the clock. It’s about the friction in our days.

It’s been a whirlwind stretch since my last post. In the span of a few weeks, I found myself juggling family and work in equal measure: a week at the American Sociological Association (ASA) conference in Chicago, my mom’s heart attack (she’s thankfully on the mend), and the start of my new role teaching at Clemson University. With all that happening, my writing here had to take a back seat.

But I’m back, and in this post I want to share the ideas I presented at ASA. The research comes from my long-running project on elite professionals and time. I’ve written before about fragments of this work, but what I shared in Chicago—and what I’ll unpack with you now—pushes the project in a new direction. The key insight is this: inequities of time aren’t just about hours or schedules. They’re about friction: for some, tensions over time get smoothed away by invisible buffers; for others, the stress caused by time sticks, slows, and scars.

“You get so much done. You have more clients than anybody else. Your calendar’s a disaster, but you get it done,” Tyler’s colleagues would tell him. As a management consultant, Tyler brushed these comments off as if his performance were simply a matter of will: “You could do that too. You just choose not to.”

However, a closer look reveals that Tyler’s edge comes from structural advantages, not personal grit. As a senior executive, he had the freedom to rearrange his schedule without pushback. Access to high-level technology kept his projects moving even when he was absent. And “proxy workers” picked up tasks in his place, often without receiving acknowledgment. These buffers made his path look smooth and deadlines appear effortless. But what looked like skill was really privilege camouflaged as competence.

Three Ways of “Doing Time”

In my interviews with elite professionals across tech, finance, consulting, and media, I found not one but three dominant ways of performing time.

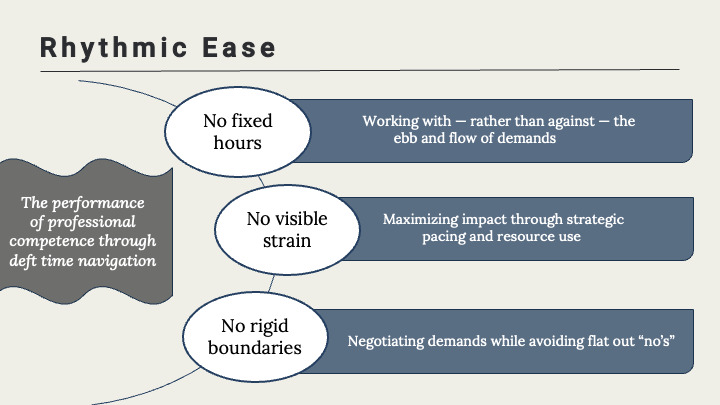

Rhythmic ease isn’t about working longer hours but about timing—riding the wave of work’s peaks and valleys. Those like Tyler practicing it didn’t draw rigid boundaries. Instead, they bent deadlines to fit their priorities, pacing themselves to match the tempo of the workplace. It was often summed up as “working smarter, not harder.”

But that ease wasn’t just personal savvy. It rested on systemic buffers: autonomy to adjust schedules, technologies that ensured work progressed smoothly, and support staff who absorbed tasks. Because rhythmic ease aligned so seamlessly with elite workplaces, its many supports faded into the background. The synchronization disguised the scaffolding. This mirrors sociologist Shamus Khan’s broader concept of “ease”—the way structural support gets mistaken for individual skill, feeding the myth of meritocracy and justifying inequality.

Managed absence was used by workers with responsibilities they couldn’t easily adjust or hand off. These professionals made their time away highly visible in hopes of slowing the firehose so they didn’t fall further behind. It was a way to cope with a constant feature of elite workplaces: the endless flow of work.

But by drawing rigid boundaries around when they were not available, they risked disrupting the smooth flow of elite workplaces and revealing the rough edges in institutional processes. Work still had to be covered, leaving teams to grind through the gaps. Compared to colleagues with rhythmic ease, their approach was seen as the problem. As a result, their divided commitments—rather than institutional shortcomings—came under scrutiny. They often faced what sociologists call flexibility stigma—namely, workers who violate “ideal worker” norms are viewed as less dedicated and less reliable.

Conspicuous overwork—visibly working long hours—was common among junior employees, who often served as proxy laborers sustaining the rhythmic ease of those higher on the corporate ladder.

Overwork was once a badge of honor in “face time” cultures, but today it is increasingly seen as a liability, thanks to its ties to burnout. Many companies have now shifted to results-only cultures that prize output over hours. In theory, this shift is meant to reduce drag in the system and create healthier workplaces. In practice, it shifts responsibility onto individuals, turning overwork into a mark of personal inefficiency rather than a product of workplace design.

Taken together, these styles show that the workplace isn’t just about how much time people have. It’s about how their time aligns with the dominant order. Synchronization (rhythmic ease) gets mistaken for skill. Strain (managed absence and conspicuous overwork) gets punished as failure.

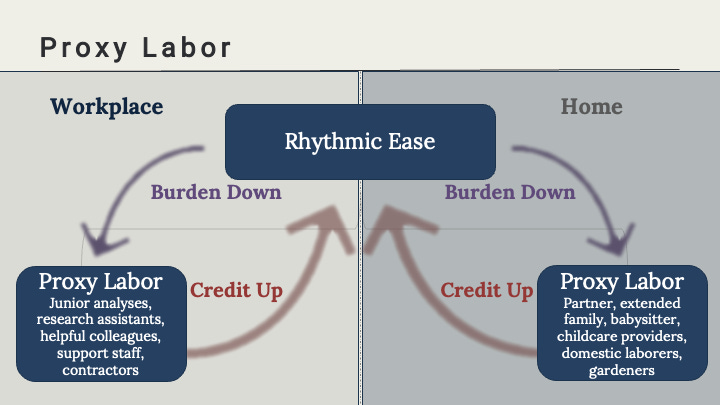

Proxy Labor

One of the core structural pillars upholding rhythmic ease is proxy labor. This is more than simple delegation. Proxy labor is when someone else does the work, but the credit—and the career benefits—accrue to someone else. It operates both inside and outside the workplace. On the clock, it might be the junior staffer who drafts the client deck the VP presents, or the assistant who manages an executive’s calendar. At home, it might be a partner, relative, paid nanny or cleaner who absorbs household responsibilities so the “employee” can move through their work week unimpeded.

However, proxy labor is not distributed equally in society. In gendered and racialized workplaces, white women and people of color are more often the ones performing it in lower-level roles, their labor flowing upward to colleagues with more power. Outside of work, women disproportionately shoulder housework and childcare, while domestic workers in the U.S. are overwhelmingly women of color. Proxy labor thus fuels the success of those already in positions of status and power—typically white men.

Proxy labor also involves a politics of visibility, as Amy’s situation illustrates. A white woman consultant who went part-time after having children, Amy struggled to balance her career with her husband’s eighty-hour work weeks as a lawyer. Their solution was hiring a housekeeper who came every Thursday.

The ability to outsource household work reflected their class position and gave Amy the capacity to sustain her consulting career. But acknowledging that help risked undermining her credibility under traditional gender norms, which still expect women to “do it all.” So Amy wound up “jokingly” thanking her husband for doing the laundry on Thursdays. “He is sharing,” she explained, “by paying someone else to share for him.”

All joking aside, in making him the visible beneficiary of proxy labor—and thus erasing the housekeeper’s labor as well as her own—Amy protected her own standing while reinforcing her husband as both breadwinner and engaged father: a win for him in both traditional and progressive terms. Proxy labor thus functions as a quiet engine of rhythmic ease—transferring burdens downward, credit upward, and in the process disguising privilege as skill.

Why It Matters

Elite workers matter because their practices become the cultural standards the rest of the labor force is measured against. But elite spaces are also sites of profound inequality. The very practices that make (some) elites look effortlessly skillful are sustained by hierarchies within their own ranks — hierarchies of gender, race, and role that shape who gets seen as productive, who is seen as inefficient, and who is made invisible. So when elites set the standard, it’s not only a standard few can meet, it’s also one built on unequal foundations.

The bigger picture that emerges is that when we treat time as just another resource to be optimized, we miss the structural contexts that shape it. That’s why inequality research so easily gets turned into fodder for apps and hacks promising you can “do more with less.” But it turns out that we don’t all have the same 24 hours. Some hours glide by because others are carrying the weight. Others bend to fit the needs of elites because those without power can’t say no. Until we see how friction is distributed — who absorbs it, who escapes it — we’ll keep mistaking privilege for hustle and structural advantage for personal failure.